Revealing glimpses into the heart of panel paintings

Twelve of the extant forty paintings by Bruegel are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Twelve panel paintings have now been analysed and studied using state-of-the-art technologies in a long-running research project. For the first time, we have looked at materials, the artist’s creative process, handling and technique, and at the changes and interventions these paintings have suffered over the centuries. The findings are fascinating.

Like many of his contemporaries, Bruegel executed his paintings on panels.

As part of our research project we used dendrochronology, a scientific method to date trees from their growth rings and to identify their provenance.

As expected, Bruegel carefully selected the planks he used as supports for his paintings. We discovered that the trees had grown in the Baltics, in areas that are now parts of Poland and Russia.

This was high-quality material. Baltic oaks grow slowly and ramrod straight, which means they produce particularly stable and long planks.

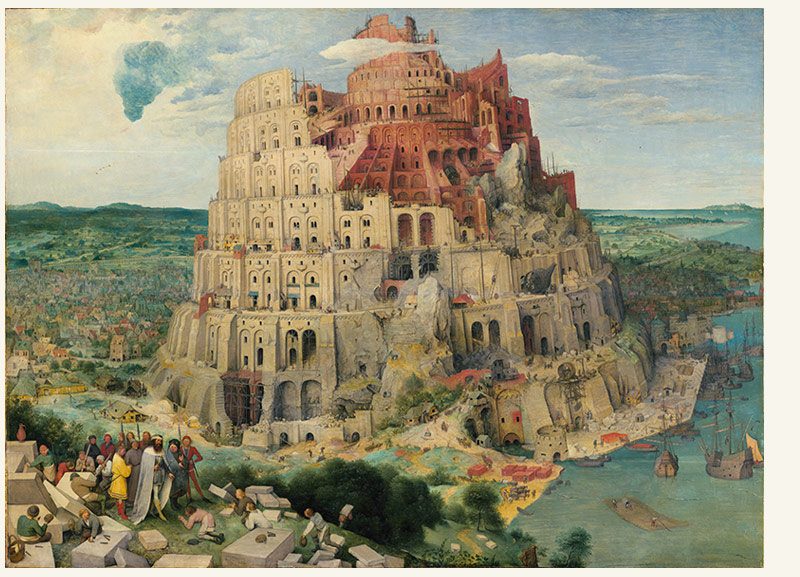

The earliest growth ring we found dates from 1201! This plank was used for The Tower of Babel.

However, the planks for The Return of the Herd, Peasant Wedding and The Birdnester are more recent. Here, the youngest growth ring we found dates from 1546. It is fascinating to note that at least 13 years elapsed between the youngest growth ring and the date on the painting.

We did not find any instance of planks from the same tree being used in different paintings. Sometimes, however, Bruegel selected planks from different trees for a single picture.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

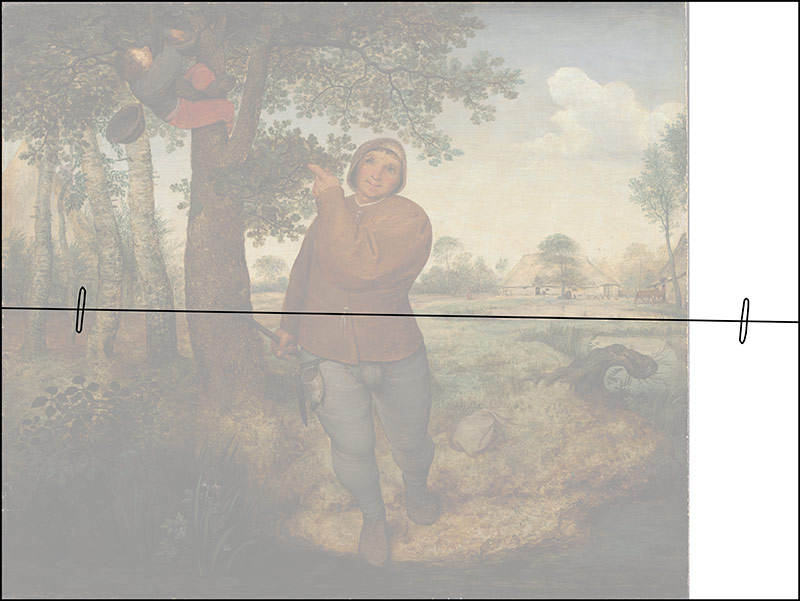

The Birdnester

1568 // Signed and dated at lower left (in gold-coloured paint): BRVEGEL M.D.LXVIII // Oak panel, 59.5 × 68.3 cm // Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Picture Gallery, inv. no. 1020

Unimaginable today but once quite common – cropping a painting

Over the centuries, Bruegel’s masterpieces had much to endure. Only one of the twelve panel paintings has retained its original format: Christ carrying the Cross. All the others were cropped – some more, some less.

The unframed Tower of Babel clearly reveals that someone has taken a saw to the panel’s top and right edges.

Initially, the tower did not ‘pierce’ the upper edge as much as it seems to do now. The tower’s unfinished right half and the huge shadow it casts to its right are more prominent.

The format was greatly altered.

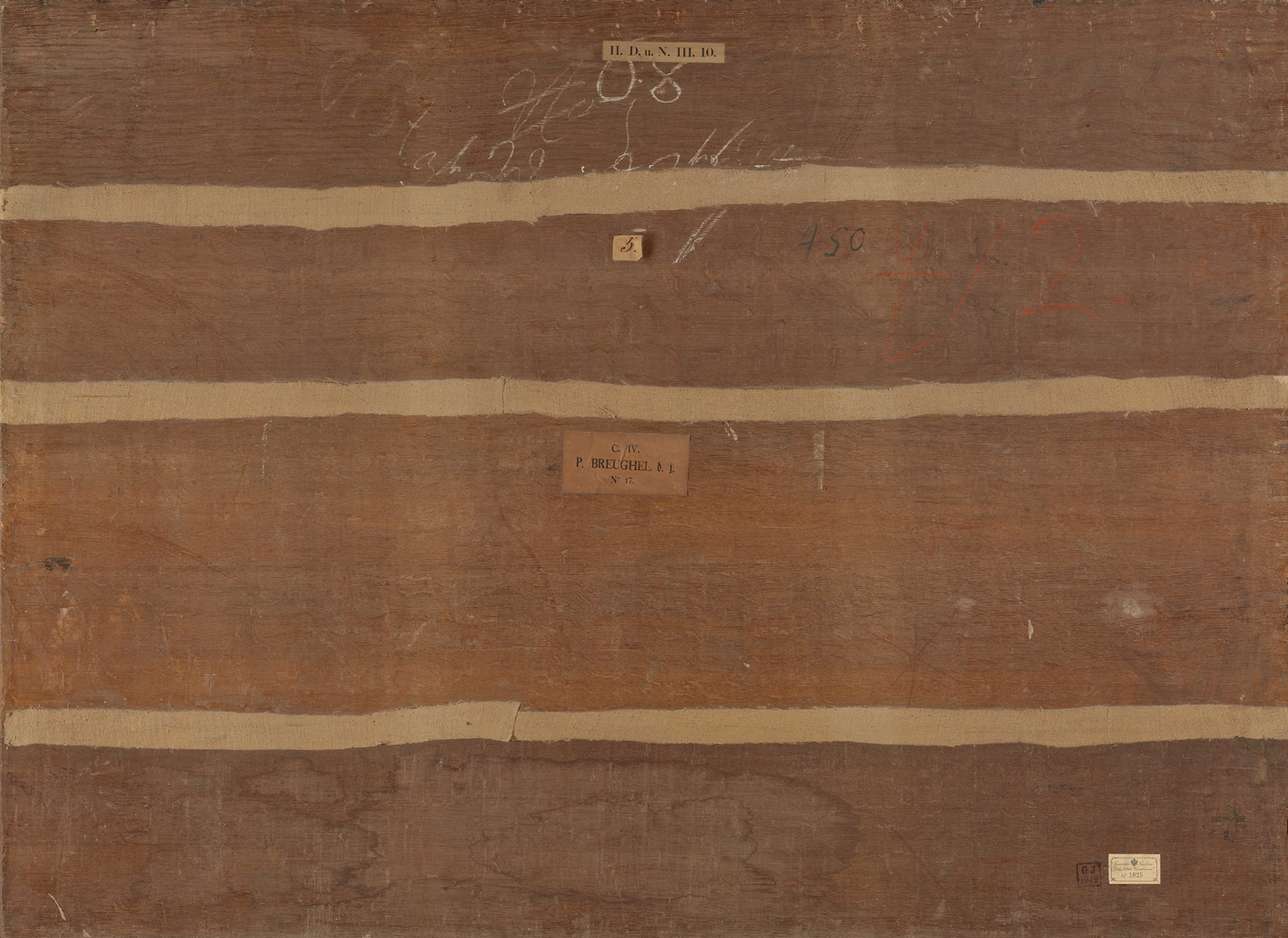

With other works, the changes in format are less apparent. Here, modern technologies and X-rays allow us to look inside the panel paintings. Among much else, they reveal dowels. These tell us about the painting’s original format.

We now know that The Birdnester was severely cropped, greatly altering its appearance.

Today, the birdnester has moved to the centre of the composition. While this may have achieved greater balance, the landscape has become less prominent.

Be that as it may, Bruegel’s carefully calibrated composition has been radically altered.

Today, we would call such interventions wanton. In light of these acts in addition to threats like fire, war and other external dangers, it seems almost a miracle that all these works by Bruegel have survived the centuries more or less intact. However, only four of his ’tüchlein’ have survived.

Originally, these ‘tüchlein’, which he executed in distemper on fine cloth, formed a seminal part of Bruegel’s oeuvre.

Well-intentioned but misguided attempts at stabilization

The paintings were also subject to conservation measures that were carried out with the best intentions. In the nineteenth century, eight of Bruegel’s paintings were cradled in an attempt to stabilize them. For this, the reverse sides of the panels were sanded, in many cases severely reducing their thickness. Slats were then glued onto the back of the painting. It was believed this would help reduce warping or stabilize fragile panels.

Of course, the reduction in the panel thickness often resulted in even greater problems.

Again, only Christ carrying the Cross has been spared and has retained its original thickness. This painting therefore plays a significant role in attempts to reconstruct the original construction of the panels.

This is why both its front and reverse sides are on display in the exhibition.

Once the planks had been selected and joined with dowels, the format determined and the composition finalized, Bruegel began to apply the ground.

The ground comprised chalk with an animal glue binder; it was applied in several layers and then sanded to create a smooth surface. This is typical of contemporary Netherlandish painting.

The pale ground is an important element of Bruegel’s technique and handling. It reflects the light coming through the paint, so that the colours appear more luminous. The artist creates the illusion of depth.

What does this tell us?

Using non-invasive methods like infrared-photography and infrared-reflectography to analyse the underdrawing was an important part of our research.

What do these findings tell us? Identifying the kind of underdrawing Bruegel executed, and knowing whether he stuck to it or altered numerous details, allows us to make inferences about his creative process.

In his early works, Bruegel paid special attention to and carefully delineated the countless miniature-like details he included in his compositions. We can see this for instance in The Battle between Carnival and Lent.

Here, we can identify delicate outlines, and even tiny details such as fingers or skewered sausages are delineated. When he painted then, Bruegel stuck closely to these underdrawings.

Bruegel’s brushstrokes become much freer, however, in his rendering of the stage – i.e., the houses lining the main square. Here, too, he executed underdrawings but then decided not to adhere to them.

It seems as though Bruegel began by freely creating a stage, which he then proceeded to fill with tiny details.

He changed his approach for Children’s Games, painted only a mere year after The Battle between Carnival and Lent. Here, Bruegel relied on preparatory drawings for far fewer details.

The Tower of Babel from 1563 represents a break in his use of underdrawing. Here, Bruegel felt free to ignore his own preparatory drawings, introducing countless changes while working on the painting.

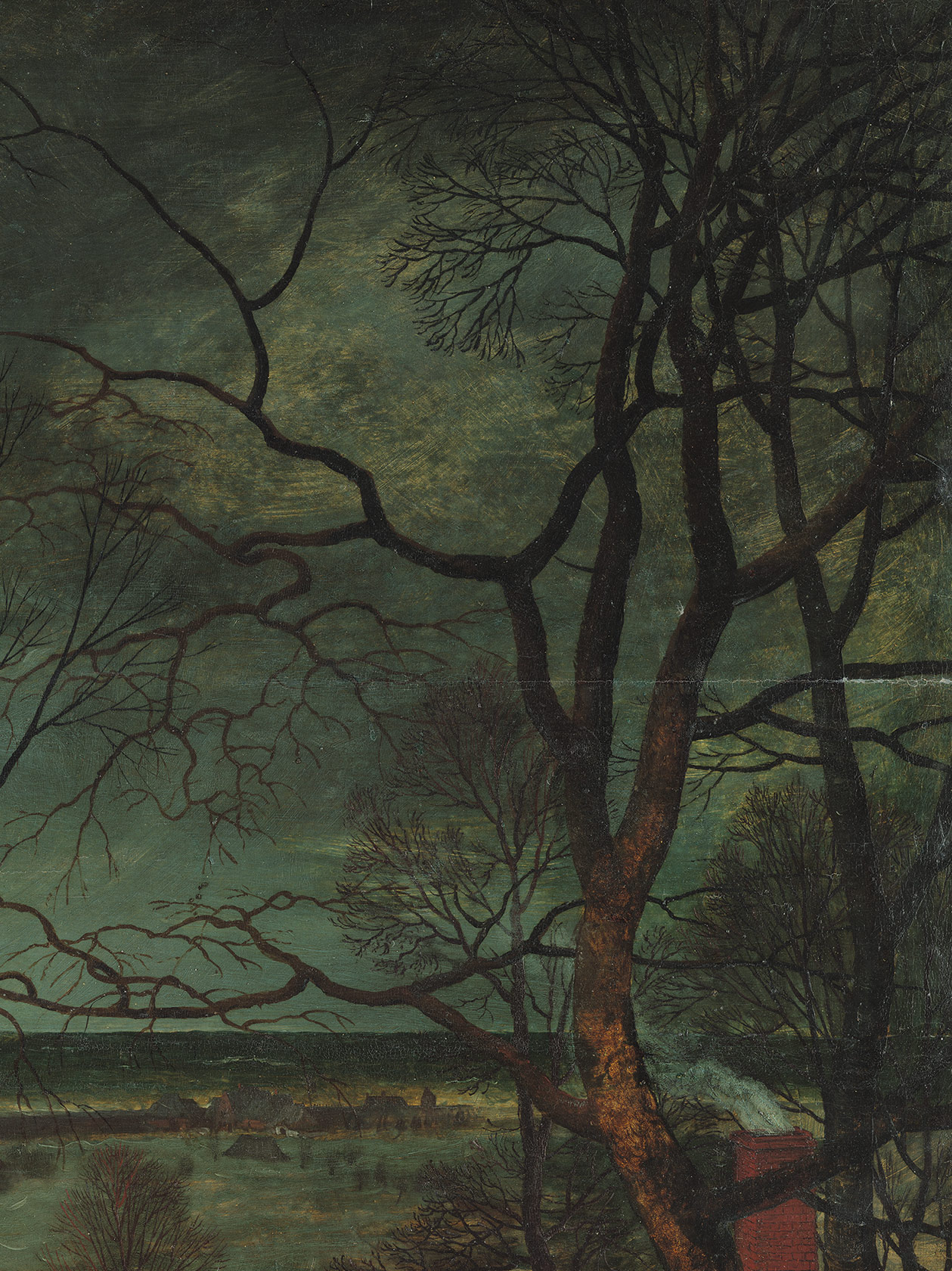

Why do Bruegel’s landscapes draw us into the depth of the composition? How does Pieter Bruegel the Elder manage to produce this incredible feeling of space and depth?

It is impossible to construct a landscape with a low horizon line while strictly applying the laws of perspective. This requires a different approach.

Following an established tradition in Netherlandish painting, Breugel constructed his landscapes in layers from the back. Details in the foreground thus hide more distant ones. The trees are a very good example: some of the branches further back, which Bruegel had painted first, are hidden or obscured by those in the foreground. This detail from The Gloomy Day is an excellent case in point: by adding, superimposing or incorporating branches, Bruegel created the illusion of space and depth.

Bruegel’s use of colour

Bruegel’s choice of carefully graded hues also helps to create the illusion of space and depth. He selected different palettes for each of his paintings. In The Battle between Carnival and Lent, for example, he used a surprising amount of black. Children’s Games was executed in pale, warm, glowing colours. The wintry mood in Hunters in the Snow is borne of warm yet frosty shades of blue.

What did the colours consist of? The pigments are typical for the time of Bruegel and his native country: the X-ray fluorescence analysis revealed earth pigments in the red and yellow ochres and umber, lead-tin-yellow, vermillion, bone black, plant black and, of course, lead white. Green was usually produced by mixing azurite and lead-tin-yellow.