Radical details

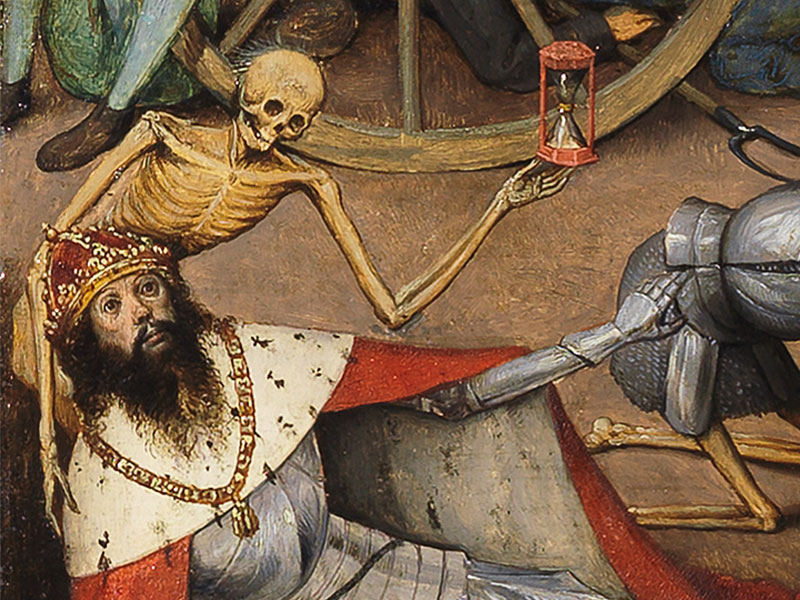

There are countless details in Bruegel’s compositions, which are frequently employed by the artist in order to convey a radical message. Sometimes they are gruesome like the details in this, probably Bruegel’s bleakest composition: The Triumph of Death.

For whom the bell tolls

Skeletons are taking over the world, spreading horror and panic. This terrible vision is the reason Bruegel is often compared to Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450 – 1516 ‘s-Hertogenbosch).

This apocalyptic landscape, filled with burning cities, foundering ships and a desolate wasteland, is also reminiscent of Joachim Patinir (c. 1485 Dinant(?) – 1524 Antwerp).

In the lower half of the composition, Bruegel has arranged a dense, anonymous crowd inexorably surging forward from left to right. Regardless of age, gender, ancestry and rank, no one can escape when his or her time is up. The mad rush ends in a ‘death trap’: people are driven there in droves. The inside of the flap door is marked with a large crimson cross. The entrance is flanked by an army of skeletons. Their shields are coffin lids.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The Triumph of Death

Probably after 1562 // Panel, 117 × 162 cm // Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, inv. no. P01393

Dare to take a look?

Discover more details with us:

The Prado has recently completed the restoration of The Triumph of Death especially for the exhibition in Vienna. This is the first time it is shown together with Dulle Griet, which has just been restored at the KIK IRPA The Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels. This promises to be another important step in research of the presumed connection between these two paintings.

Dulle Griet2

Dulle Griet or Mad Meg

This is another composition that is not for the fainthearted. Many of the details are reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516), and rather macabre. However, the painting is also infused with Bruegel’s sense of humour and his wit. Dulle Griet, for example, sports armour and brandishes a sword. A dagger dangles from her apron. For good measure, she is also carrying the ultimate weapon: a frying pan.

We do not know if Pieter Bruegel the Elder selected this subject matter or if this was a commission. We may assume that Bruegel was poking fun at the hierarchy between men and women.

He inverted the traditional gender roles prevalent in the Low Countries during the sixteenth century. This composition is not the only one in which he did so: Bruegel also produced countless illustrations of cunning women who are literally and figuratively wearing the breeches.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Dulle Griet

1563 // Signed lower left: BRV[E]GEL MDLXi[ii] // Panel, 117.4 × 162 cm // Antwerp, Museum Mayer van den Bergh, inv. no. 788